What?

What will your think tank do?

In this chapter we discuss several questions that will help you define what exactly your think tank will do. As we have seen, think tanks can fulfil many functions so you need to be clear on what your goals are. We recommend that as soon as you start working on the goals of your think tank you spend time analysing your context. Local and global contexts will condition what your think tank can do, and understanding these will help you identify different strategies.

What is the context? (+)Based on: Brown, E. (2015), Introduction to the series on think tanks and context. Learn more(+)Ordoñez, A. and Echt, L. (2016), Module 2: Designing a policy relevant research agenda. From the online course: ‘Doing policy relevant research’. On Think Tanks. (+)Mendizabal, E. (2016), Setting up a think tank: step by step. Learn more(+)Garcé, A., D’Avenia, L., López, C. and Villegas, B. (2018), Political knowledge regimes and policy change in Chile and Uruguay. On Think Tanks Working Paper 3. Learn more(+)Tolmie, C. (2015), Context matters: So what? Learn more

Think tanks are a product of, and intertwined with, their context. An organisation’s research choices, functions and even its impact are a response to its context. The context will frame and influence the research agenda, the communication strategies, and even the ways of engaging with the think tank’s key audiences. Think, for example, how the global context of the COVID-19 pandemic changed almost every mode of engagement and shifted the priorities of both governments and funders.(+)For more on the effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on think tanks see Mendizabal (2020) COVID-19’s effect on think tanks in 10 headlines Learn more(+)Explore this collection of articles. Learn more

- Context will affect an organisation at every level, in all its functions and characteristics. It is therefore fundamental to assess it early on so you can:

- Identify if your ideas (about the challenges or opportunities you want to address) are relevant.

- Assess your real capacity to have influence.

- Position your efforts in the context of relevant current trends (evidence needs, policy gaps, donor priorities, etc.).

- Map out ‘the competition’ and assess who you might be able to partner with and who is likely to challenge your project.

- Analyse local, national and international spaces for action.

- Understand what roles a new think tank could possibly play.

- Decide what type of think tank you should create and how it should operate.

For example, in Bangladesh and Vietnam, political competition affects how think tanks relate to political parties, just as deciding whether to affiliate to a party or remain independent affects their effectiveness (Brown, 2015). In Vietnam, think tanks cannot be completely independent from the government; they need a sponsor to help them achieve their objectives. This is similar to the situation in China, where think tanks are deeply intertwined with the government and the Party and cannot function in absolute independence. In the United States, on the other hand, think tanks need to engage with philanthropists and the private sector to secure funding because financial separation from the government is considered essential.

Basically, all think tanks are embedded in a context that frames their work. No matter the sort of organisation that you aim to create, you will be acting and functioning within a system, and therefore you need to be realistic. You will not be able to change the whole system, but you may be able to shape parts of it.

Thus, when analysing your context, you should also consider the future. Take the time to think about what future you imagine for your think tank: what landscape do you imagine five years down the line? This will help you reflect up front on what could go wrong. You should start considering the different risks you may face and how you could address them.

There are also the policymaking and knowledge regimes that need to be accounted for. Knowledge regimes are ‘the organizational and institutional machinery that generates data, research, policy recommendations and other ideas that influence public debate and policy-making’ (Campbell and Pedersen 2014). To determine the local knowledge regime, you need to understand the policymaking regime (how policies are developed), the economy, the politics, and the social and cultural characteristics of a country – as these all influence the market of ideas and how research is produced and used. To understand how knowledge is produced, and used in politics and policymaking, all of these variables (and their importance in a context) need to be accounted for. But how does the policymaking regime affect think tanks? Think about how, for example, Germany has a strong tradition of using research to inform policymaking, and its citizens and policymakers value the role of knowledge in policymaking. On the contrary, in Uruguay, politics trump technical reasoning; while in Chile, knowledge plays a vital role and creates bonds between political parties and interest groups (Garcé et al., 2018). (+)For more on policy and knowledge regimes read: Campbell, John L. and Ove Pedersen (2014), The National Origins of Policy Ideas: Knowledge Regimes in the United States, France, Germany, and Denmark. Princeton: Press Princeton University Press. Garcé, A., D’Avenia, L., López, C. and Villegas, B. (2018), Political knowledge regimes and policy change in Chile and Uruguay. On Think Tanks Working Paper 3. Learn more

Box 12. The importance of local contexts

Dr Asep Suryadhadi, executive director of SMERU (Indonesia) was interviewed by Vita Febriany in 2013. He discussed the importance of understanding the context when establishing a new think tank. Read the full interview here.

“One thing that I have learnt is that context matters a lot. SMERU was established when Indonesia was in a transition from an authoritarian governance, where the government can get away with any policy they make, to a democratic governance, where every government policy is openly questioned and debated. This means now that the government needs evidence as the basis of any policy they make. On the other hand, there were not many of organizations capable of supplying evidence for policy. With this background of increasing demand and lack of supply of evidence, SMERU was able to capitalize the situation and develop itself into an established policy research institution in the country.

So it is very important to understand your context. We cannot just copy successful think tanks in other countries as a model because it may not work in our country. This is not to say that we should not learn from other organizations as certainly there are useful lessons that other organizations can provide. However, by understanding our context, we will be able to set reasonable objectives that we want to achieve as well as determine how we can operate effectively and efficiently.”

Box 13. Changing context

Chukwuka Onyekwena, executive director of the Centre for the Study of the Economies of Africa – CSEA (Nigeria) was interviewed by Enrique Medizabal in 2021. Listen the full interview here.

“In general, the internal policies that I met in the past years was one where the demand for evidence was quite weak. Over the years, the demand was increasing gradually within the policy space. Think tanks have tried to really push to stimulate the demand for evidence. We thought that Think Tank initiatives which provided flexible funding allowed Think Tanks to emerge within Nigeria (…) As the availability of flexible fundings have been declining, now Think Tanks are struggling. The ability to stimulates evidence is now being unlimited. But that is also changing recently due to COVID. COVID is a shock. People from the policy space needed knowledge to explain what is going on, the impact, what strategy should we use to solve this challenge that is quite rare. Knowledge produced by Think Tanks became increasingly involved in providing adequate advice or recommendation on what to do. So COVID-19 arrived and increased the demand for knowledge and Think Tank has benefitted for that (…) Shocks tend to change the way we do things. For example, financial crisis was a big shock and a lot of accounting principles changed. COVID will change how policy actors view things, how they look at the future and how they prepare for such shocks. Think Tanks have the opportunity to be at the forefront of these kind of conversations. So, it will really trigger higher demand for evidence.”

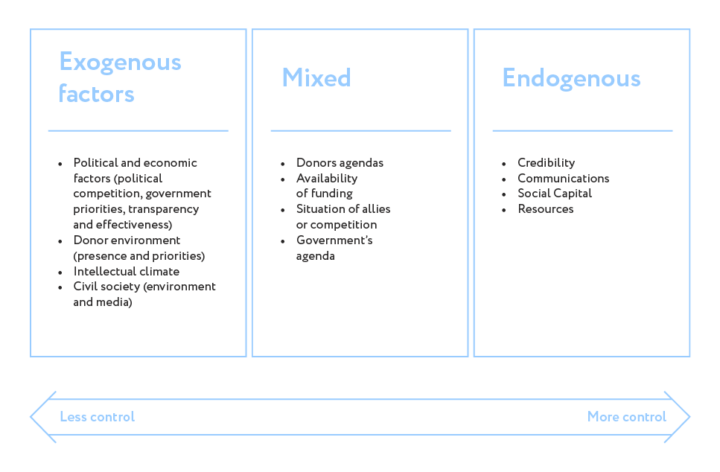

But how do you make sense of your context? What factors should you consider? In their publication Linking think tank performance, decisions, and context, Results for Development (2014) devised a framework for thinking about context as it relates to think tanks and their decisions. The framework describes different levels and factors that explain how think tanks make decisions based on their context. Ordoñez and Echt (2016a) have provided a summary of the framework, shown here in Figure 1, to help organisations reflect on their environments. The framework differentiates between exogenous, endogenous or mixed factors, based on the level of control that an organisation can exert.

- Exogenous factors: are ‘factors that are determined by forces outside of the think tank’s sphere of influence and that impact the think tank’s ability to achieve its goals’ (Brown et al, 2014). For example, the number and strength of political parties, an authoritarian government, and turnover in key government positions, among many others, are all exogenous contextual factors that will affect what a think tank can do (Brown, 2015).

- Endogenous factors: are internal to the think tank and therefore under the control of the organisation, even though they are still influenced by the context. For example, hiring top-level staff is something that is largely under the control of the think tank but is influenced by the context: availability of adequately trained and experienced individuals, labour laws, the location of the think tank (capital or smaller city), and so on.

- Mixed factors: include circumstances in which context is partly a function of a think tank’s strategic choice and partly a function of variables outside of its influence. But think tanks do not just passively accept their context: they are a product of their context, but they also seek to change it. They create strategies to respond to it; they use their communication, research, and policy engagement tools to address their contextual factors and react to them (Tolmie, 2015).

Figure 2. Context levels

Source: Developed by Ordoñez and Echt (2016b) based on factors proposed by Results for Development (2014) and adapted by the authors of this guide.

Analysing your context: Key questions to reflect on (+)Based on: Mendizabal, E. (2015b), How does the context affect think tanks? A few hypotheses and research questions. Ordoñez, A., Echt, L. (2016), Module 2: Designing a policy relevant research agenda. From the online course: ‘Doing policy relevant research’ On Think Tanks. Learn more

It is important to reflect on these contextual factors while thinking about the organisation you aim to create. Remember to focus on the aspects that help explain the situation that the think tank will be born into, and the aspects it will try to address. To do this effectively you will need to be selective of the dimensions that you include in your analysis (Ordoñez and Echt, 2016a) and reflect on what the answers imply for the work that you intend to do, including how you will conduct research and communicate your findings.

Here are some questions that can help you analyse your context (building on Ordoñez and Echt, 2016a; Results for Development, 2014; and Mendizabal, 2015)(+)The headings do not exactly follow the 2014 Results for Development framework. We have adapted them and highlighted some factors to help reflect on the context your think tank will be born into. :

Political context

- What are the characteristics of the political system in which you are involved? How does the political system react to independent thinking? How do actors react to the type of work you aim to produce?

- What are the main changes occurring in the political, social or economic systems? Are there any major developments or trends taking place? (e.g. democratisation, regionalisation, changes in economic policies, migrations, etc.)

- Are there any relevant policy or political milestones expected in the short or middle term? Are elections coming up? Is there a 5- or 10-year development plan in place? Is a new constitution or trade agreement being drafted?

- What actors would you need to engage with? Who is most relevant at the local, national and/or international level?

Evidence needs and access to information

- What is the state of the information on the topic you are choosing? What kind of information is available? Would we be able to carry out the necessary research to address any knowledge gaps?

- What contacts are available to you to access data or assess evidence needs?

- What are the interests, worries and capacities of public agencies regarding the use of research in policymaking? What are the needs of government institutions in terms of research? What are their capacities to generate, demand and use research? How can you start a discussion with them?

Funding

- What are the priorities, strategies and objectives of funders? Who supports the issues you are interested in? Who can you approach?

- What are the international trends in academia or policy? How will you relate to them to make your work more fundable?

- Are there any national, regional and global sources of public and private funding that you may be able to benefit from? What conditions are attached to them?

Intellectual climate

- What is the intellectual climate like? How is science valued? Is it considered valuable for policymaking? How do intellectual debates take place? Is it the same for all policy issues, or do some have bigger and more active intellectual communities?

- What will your relationship with other intellectually relevant actors (such as academics, journalists, opinion leaders, experts in your field and others) be like? Will there be competition, debate or will you complement each other? How can you work together if necessary?

Civil Society

- What is the role of the media? Is it free? Is it overtly partisan?

- What other players foster the dissemination and use of evidence? Are there any academic communities with an active role in policymaking? Who are they? Who has more credibility Why?

- Is there a demand for evidence from civil society organisations? What type of evidence do they prefer? Is civil society familiar with the evidence-informed approach that think tanks promote? What is their stance on it?

- Is there demand for evidence from social movements and other grassroots organisations? What type of evidence do they prefer? Are they familiar with the evidence-informed approach that think tanks promote? What is their stance on it?

- What is in the agenda of other research centres, universities and think tanks?

Regulatory regimes

- What are the regulatory frameworks that affect think tanks and research organisations? How do they enable or limit their ability to mobilise resources, human or financial? How do they enable or limit their ability to influence policy and practice?

- How will labour legislation affect your organisation? Does it permit flexible work contracts? Will you be able to hire globally?

- What is the tax legislation like? (Think not only in terms of how it affects the organisation but also potential donors). Does it encourage or discourage philanthropists to support research? Does it limit the activities think tanks may undertake (for instance, to maintain tax exemptions)?

- How does the exchange rate affect you? (crucial to consider if you have foreign funders)

- How does civil society legislation more broadly affect think tanks?

Other practical issues

- Is internet access widespread and reliable?

- Will you have access to online databases, academic journals, communities of practice etc.?

- Will you be based in a large or a small city? Will it be in the capital or in another part of the country? How will this affect your access to policymakers, the media or other relevant actors The definition of your location will be influenced by your goals and your desired level of influence.

- What is transport like within the city or to other cities? Will traffic affect the types of activities you wish to organise? For example, you might not be able to organise too many events if traffic limits mobility in the city.

- How does the education policy affect think tanks? Is critical thinking a value? Are research methods and writing well taught? These factors will affect the quality and quantity of researchers available to work with you.

What do you want to achieve by setting up a think tank? (+)This section draws from these articles Mendizabal, E. (2013b), Strategic plans: A simple version. Mendizabal, E. (2016), Setting up a think tank: Step by step.

Once you are firmly situated within your context and have a firm sense of how it will affect your future organisation, you should ask yourself ‘what would you like your think tank to achieve?’ (+)We have explored context before starting to look at the organisation’s aims, because the context will frame what it will be able to achieve and how. . To answer this we recommend you reflect on the vision and the mission of your organisation, which are framed by your values.

Vision

The vision is your dream, the ideal world, the big picture of what you would like the think tank to achieve. It is not something that will be achieved in the short term. It should be visionary but at the same time realistic. Here are some examples:

‘Our vision is a world in which government, politics, business, civil society and the daily lives of people are free of corruption.’ Transparency International, Germany.

‘We envision a world of democratic freedoms and fair and sustainable development through European integration and international cooperation.’ Istituto Affari Internazionali, Italy.

Mission

The mission is the organisation’s purpose; it is what the think tank will do to contribute to the achievement of the vision. A good mission need not be lengthy. On the contrary, a short, powerful and clear mission is preferred. For example:

‘EPI’s mission is, through high-quality research and proposals on European policy, to provide a sound base for debate and solutions, targeting decision-makers and the wider public’ European Policy Institute, Macedonia.

‘Centre for London is the capital’s dedicated think tank. Our mission is to develop new solutions to London’s critical challenges and advocate for a fair and prosperous global city’ Centre for London, UK.

‘Using our knowledge, networks, funding and skills, we work hard to see new opportunities and challenges; spark creative answers from many sources; shape brilliant ideas into practical solutions; and then shift whole systems in a new direction’ Nesta, UK.

‘Our mission is to produce knowledge, propose initiatives, develop practices and support processes to contribute in the construction of a stable and lasting peace in Colombia’ Fundación Ideas para la Paz, Colombia.

‘To be recognized as an innovative institution that is committed to Brazil’s development, the formation of an academic elite, and the generation of public goods in social and related areas, guaranteeing our financial sustainability through the provision of high-quality services and high ethical standards’ Fundação Getúlio Vargas, Brazil.

Values

The values are the guiding principles and the foundation on top of which all actions rest, whether formally identified or not. They are beliefs about what is important, and the way to act. No individual or organisation is without values. Even independence, neutrality, and being led by data are values in themselves:

‘Everyone has them [values]. And every time that a think tank recommends a course of action it is making use of values: evidence does not tell us what to do. It informs and is the basis of our analysis to recommend courses of action’ Mendizabal, 2016 (+)For more on this read: Mendizabal,E. (2011), The limits of the scientific method and the need to merge science and innovation Learn more.

It is helpful to identify your own values in the early stages. They do not need to be specific to the point of limiting your actions, but should offer a sense of where your organisation might fall in the political spectrum. These may be rather simple (e.g. all for liberalisation) or more complex (e.g. liberal on social issues but more conservative politically and moderate on the economy) (Mendizabal, 2016)

Through our work with think tanks and policy research organisations we have found that organisations tend to publicly frame their values not in terms of where they stand on the political spectrum, but rather by focusing on how they undertake their work. What values will underpin the way you work? Here are some examples to help you understand this:

‘Independence: The independence of our thinking, as much as its rigour and creativity, is what makes it influential. Inclusivity and diversity: We ground our analysis and solutions in an inclusive approach. We bring diverse voices to the table to find common solutions to shared problems. We ensure our research and outputs are widely accessible, so people can develop their own voice in international affairs. Collaboration: Collaboration is a core competence for our staff. It inspires our relationships with associates, partners, supporters and members and helps us develop global networks to find positive, durable solutions to policy challenges’ Chatham House, UK.

‘What we stand for: Independence. Excellence, Relevance and Innovation. Cross-cutting and Long-term Solutions. Multi-constituency and Inclusive. Partnership and Outreach’ European Policy Centre, Belgium.

‘The values that define CIDOB’s work are: The desire to act as a public good through the provision of international knowledge. Excellence, through the rigour, quality and independence of our analysis. Innovation in the approach to studying international relations. Visibility, via new research formats and media presence. The promotion of the good management and economic health of the institution and the proactive search for new projects’ CIBOD, Spain.

You do not need to put your vision, mission, and values in writing – certainly not laminated. But working on them is highly recommended as they will certainly frame the work that you do. Also, having a clear mission will make planning a strategy easier. It will make your organisation more attractive to the likeminded individuals you want to work with, and it will draw attention and support from funders interested in the same issues (Mendizabal, 2016).

Box 15. What does the ‘About us’ section usually convey?

The ‘About us’ section of a website is an opportunity to showcase your organisation. What gets included, and also what gets left out, signals to readers (be they funders, academics, policymakers, activists, or the general public) who you are, what is important to you, and what they should expect from you.

We have found the best ‘About us’ sections include: who the organisation is (organisational structure, affiliations etc.), what the organisation does (main issues, functions), how it does it (key expertise) and why. The style is also important, and keeping it simple, descriptive and to the point tends to work best across all cultures. Here are some examples of content from various ‘About us’ pages:

The Brookings Institution describes who they are (experts, leaders, history and agenda), what they do (annual report, selected essays, and fellowship programme), and what they stand for (policies on integrity, diversity and inclusion and public health funded research)

The Center for Global Development highlights their mission and values, their impact and influence, leadership, board, directors, working groups data disclosure, funding and history. They also invite visitors to find out more about working with them and supporting them. They have specific sections for educators and the press, where they highlight resources tailored for them

The Nesta Foundation has an inspiring 100-second video that covers what they aim to do, what they stand for, and how they do it. For those who want more details they also explain how they work, what they want to achieve (phrased as questions on the topics that they are covering), their innovation methods, services, and their international work, and introduce their team.

The German Council on Foreign Relations describes their aims and the themes they work on, invites the reader to join the organisation as a member and introduces a journal that they publish as well as their library. There are also links to their board, statute, history and code of conduct.

What issues will the think tank focus on? (+)This section draws from these articles: Mendizabal, E. (2016), Setting up a think tank: Step by step. Learn more(+)Gutbrod, H. (2013a), Advice to think tank startup: Do not do it alone Learn more

In parallel to reflecting on and defining your vision, mission and guiding values, you should work on defining the issues that your think tank will focus on.

Depending on your interests and motivations, you might want to cover a broad range of public policy issues so you can address change at different levels, but we would recommend focusing on a few specific issues. Gutbrod (2013a) suggests concentrating on your own core expertise ‘either in one or two issue areas (say, health or education), cross-cutting (accountability, or budget process) or by applying a method (say, citizen report cards or surveys)’. A good place to start is by focusing on aspects that you or your team already have expertise in. It will save you time (no need to invest it in improving your knowledge or abilities in a topic you are not familiar with) and enable you to hit the ground running.

Yet, to decide the specifics you should think beyond your personal research interests and pay attention to the context and existing, or future, policy questions (+)More on this issue on the section How will it carry out research? and in the article Mendizabal, E. (2013), Research questions are not the same as policy questions Learn more, as well as to the problems you are addressing (Mendizabal, 2016).

‘Why not, too, find policy areas that are under-studied? For instance, middle class concerns. Think tanks in developing countries, funded by foreign aid donors and agencies, tend to focus on what is often termed “pro-poor issues” and shy away from more mainstream and middle-class concerns (e.g. they focus on primary education but not on tertiary education). However, as countries and their middle classes grow, their concerns need to be addressed, too. A single-issue think tank is also a good alternative. It may help you find “natural” funders and audiences’. (Mendizabal, 2016)

Another way to go about choosing the scope of your work is to consider what are the most relevant national and international policy agendas. These may be linked to international policy discussions such as Agenda 2030 and the SDGs, or they may involve specific national circumstances, such as the future of work or urban development. By linking your work to existing agendas, you will be able to take advantage of the research already done in them.

Another way to select policy issues to work on is to understand the likelihood of your research being used by policymakers. Datta (2018) summarises research conducted by ODI’s RAPID programme showing that four factors are key in shaping the likelihood that evidence will be taken up (+)Based on Datta, A. (2018), Three ways to select policy issues to work on. Learn more:

1. The level of technical expertise required to participate in policy debates. In different sectors, the need for specialised expertise may grow (e.g. climate change) in response to its growing complexity, so the demand for knowledge and experts from policymakers also increases.

2. The relative influence of economic interests in shaping policy dialogues. In certain policy areas (such as trade or social security) economic actors are arguably more prominent than in others, so it is important to acknowledge the influence of economic interests in shaping research production and uptake.

3. The level of contestation in the sector. If the area is highly contested, it will be much more difficult for research to be applied to policymaking than if there is a strong consensus about the need for policy change.

4. The extent to which policy discourses are internationalised. On many issues, local actors start to enjoy greater success in influencing policy once they being working with international players rather than only domestically.

What will the think tank want to influence? (+)This section draws from: Mendizabal, E. (2016), Setting up a think tank: Step by step. Learn more

This is strictly a what question as we are not referring to which specific audiences you will be focusing on (for that see section: Who will engage with it?). To answer this broader question, think more specifically about what policy debates you will be contributing to. At what level would you be aiming your efforts? Are you looking to have international or local influence? For example, you could be based in Serbia but aim to inform EU policy in Brussels, or be based in Lima, Peru and focus on the Sustainable Development Goals at the local level. Or you could start working at the municipal level and then shift to city level or national politics. Small doesn’t mean less interesting or important (Mendizabal, 2016).

There are many levels of influence and impact. For example, depending on the functions your think tank pursues, you may:

- Influence the definition and formulation of a key problem.

- Impact the public agenda, frame policy discussion and help define what issues should be prioritised.

- Help define the questions that fellow researchers should attempt to answer.

- Work on producing evidence to help answer these research questions.

- Make policy or programme recommendations based on evidence (either yours or produced by others) and help policymakers navigate the different options presented.

- Develop programmes or projects based on these recommendations and evidence – and, if possible, test them through small pilots.

- Develop the capacity of policymakers and other relevant policy actors to use and understand research.

- Improve how governments and ministries make decisions – which has an indirect, but equally important, impact.

- Work with the public, the media and other stakeholders to inform the debate on a particular topic, which includes changing beliefs around a specific issue.

Box 14: Local and international audiences

“International audiences are not necessarily harder than domestic ones. In Africa, some new think tanks are seeking out regional or international political spaces as a way of avoiding the challenges involved in domestic politics -especially in contexts where the policy space is rapidly closing down. The very local space is also undeserved. At the PODER Awards to the best Peruvian think tanks we have found a significant difference between the national and the local politics: the former is much better served by think tanks than the latter. In counties like Indonesia, India and Argentina, local think tanks exist to serve sub-national policy communities” (Mendizabal, 2016).

The choices you make about your desired impact or the level you want to work at (local, sub-national, national, regional, or even global), will demand different governance arrangements, different strategies, resources, and so on, and your plans will have to shift accordingly (Mendizabal, 2016). See The How? questions section of this guide, as well as What will its business model be? to continue working on this.

What does ‘using evidence’ mean in practice? (+)Based on Datta, A. (2018), Five questions to understand the evidence context Learn more

The goal of many think tank founders is to generate good quality evidence that can be used to inform policies. But evidence-related practices include more than just the application of research findings or recommendations during decision making. Policymakers may be motivated to demand or use evidence by many factors. It can be that policymakers use evidence for more personal reasons, such as to assess power gained or lost, defend or legitimise a decision, or bolster their status. They can also use it for technical purposes, such as to provide context about an issue, inform a strategy or their engagement with others, or reduce uncertainty about a policy problem.

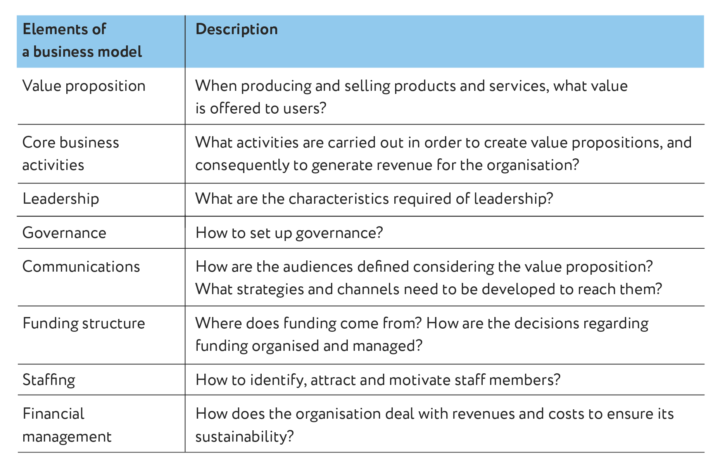

What will its business model be? (+)This section draws from: Ralphs, G. (2016a),Think tank business models: The business of academia and politics. Learn more

One of the first things you need to do is decide on the business model your think tank will follow. This decision should be based on what you want to achieve and how you want to work, but also on the context you are starting the think tank in and on the resources you have at your disposal.

A business model is ‘the way in which an organisation goes about achieving its goals… it defines the manner by which the think tank delivers value to stakeholders, entices funders to pay for value, and converts those payments to research with the potential to influence policy…. It thus reflects management’s hypothesis about what stakeholders want, how they want it, and how a think tank can use its resources to best meet those needs, get paid for doing so, and achieve its mission. In sum, a think tank business model describes the interface of a policy research institute’s rationale and underpinning economic logic’ (Ralphs, 2016a).

When developing a business model you need to make three choices: policy, asset and governance.

- Policy choices are about the internal policies that an organisation establishes for its operations. These range from decisions about flying economy, not using printers, and holding virtual vs. in person meetings, to policies such as establishing funding limits from single sources and how to recruit and retain staff.

- Assets are the tangible resources that an organisation invests.

- Governance is how the organisation will discuss and make strategic and day-today decisions (Casadesus-Masanell and Ricart, 2011).

Explore these choices further by considering the following elements (+) Learn more:

Source: Adapted from Cahyo and Echt (2015)

When reflecting on your business model, one idea is to create a story about how the organisation will accomplish its mission.

Good business models can take many forms, but they share some key characteristics:

- They are aligned and respond to the organisation’s goals.

- They are self-reinforcing, meaning that there is internal consistency. All choices and decisions should complement each other and work towards the same goal.

- They are robust. They continue to work overtime fending off risks and taking advantage of opportunities (Casadesus-Masanell and Ricart, 2011)

Remember that your business model can change if it no longer works for your organisation. See the case of Espacio Público in Box 16.

Box 16. Changing business models: The case of Espacio Público in Chile

Deciding on a business model is an important decision, one that will define how the organisation will organise and carry out its work. Business models respond to the objectives and goals of an organisation, its context and resources. Because of that, most business models are unique, and must be continually evaluated and evolving. But it is not a decision that is set in stone. If at any point the business model is not working you can make the decision to change it.

For example, Espacio Público, a think tank in Santiago de Chile, began operating in 2013 with two large core funders who provided 100% of their budget. The agreement with one of the funders was for three years and with the other funder the agreement was that they would reduce their funds every year. This encouraged Espacio Público to search for more project-based funding. By 2017 they had 20% core funding, 70% project based funding and 10% local funding.

But funding was just one of the changes they underwent. They also had to rearrange their board and their team of researchers to adapt to this project-based funding, which demands greater autonomy from the team. They reduced their team of researchers to ensure that it was composed of more senior researchers who could ‘stand before donors in their own right’ and not as assistants of someone else. In other words, as their funding model evolved, so too did their business model, in a complementary way.

Comparison of think tank business models

Research conducted by Leandro Echt and Ashari Cahyo Edi (2015) analyses the business models of six think tanks (three in Latin America and three in Indonesia) by focusing on the elements presented above. The study reveals that think tanks have different understandings of what ‘business model’ means. Some point to funding structure while others focus on the think tank’s mode of work or value proposition.

Similarities among the think tanks studied:

- Most think tanks diversify their core business activities, rather than concentrating on a single activity. These activities are usually research, capacity building and policy advice.

- Most think tanks make efforts to diversify their funding sources.

- Most organisations understand their different audiences and have communications tools to target them.

Differences among the think tanks studied:

- In terms of governance, some think tanks have heavy governance arrangements (with many internal and external bodies with specific functions) while the approach is much lighter in other organisations.

- Regarding the value proposition, for some organisations research excellence is their main product, while for others it is their ability to engage with grassroots communities.

Not everyone has the right skills to develop the business model, so it may make sense engaging a professional team to support you at this stage. Having a well-drafted business model and business plan is key to gaining the confidence of future partners and funders.

Types of think tanks (+)This section draws from: Mendizabal, E. (2013a), Think tanks in Latin America: What are they and what drives them? Learn more(+)Mendizabal, E. (2013c), For-profit think tanks and implications for funders. Learn more

The application of the different elements of a business model results in different types of think tanks. Stone’s (2005) classification, which relates to the think tank’s origin, is a good place to start. She identifies the following:

1. Independent civil society think tanks established as non-profit organisations.

2. Policy research institutes located in, or affiliated with, a university.

3. Governmentally created or state-sponsored think tanks.

4. Corporate-created or business-affiliated think tanks.

5. Political party (or candidate) think tanks.

These are just some examples of types of think tanks, and many nuances exist within each category. For instance, within independent civil society organisations, some behave like research consultancies (undertaking research on demand and even bidding on calls for proposals).

This model tends to exist where international cooperation has played a significant role or where the main research funder is the state, via requests for expert advice or evaluations. These think tanks engage in service contracts to carry out long- and short-term research projects, and because of this, their space to follow their own agendas may be somewhat limited (Mendizabal, 2013a).

Some think tanks try to combine research consultancy with more independent type communication and outreach work. (Mendizabal, 2016)

Another example of organisations that fall somewhat outside Stone’s categorisation are the for-profit think tanks we have come across in Eastern Europe, Latin America and Africa. Their context has made this the most logical business model: high upfront costs for civil society organisations, regulations that limit their free functioning or access to data, complicated tax laws for the non-profit sector, and other factors, led them to opt for this model (Mendizabal, 2013c). Many figured that while governments may try to curtail civil society, they are unlikely to do the same with small and medium size businesses.

foraus is a Swiss think tank that was set up as a grassroot organisation and reflects its origins through its extensive network of volunteers who take on policy challenges and undertake research in a very collaborative way. They are supported by a small group of young think tankers who manage these processes and fulfil core functions.

These are just some of the options that exist. Your organisation could resemble any one of these or even be different. In any case, it is important to bear in mind that the business model should work for your organisational aims and the context in which you operate and that you expect to influence.

Box 17. Types of Think tank across the world

According to the 2019 Think Tank State of the Sector, which analyses think tanks around the world, the majority of think tanks for which there is data available are non-profit organisations (67%), followed by university institutes or centres (16%), government organisations (10%), for-profit organisations (5%) and a small group of other (2%). This also varies by region. For instance, in China the percentage of government think tanks is 74% while in the US and Canada 97% are non-profit. The legal registration of your organisation will need to adapt to the context in which it will operate (see What is the context? for more on this discussion)

Box 18. Think tank models in Zambia

As examples of the diverse types of think tanks that exist, we present a summary of different think tank models in Zambia (based on Mendizabal, 2013d and 2013e).

Academic think tank

These are the most traditional, and preferred by funders such as the African Capacity Building Foundation (ACBF). They follow an academic model and tend to be rather expensive (funding wise). ZIPAR (Zambia Institute for Policy Analysis and Research) is an example of this type. It had a slow and steady early start focussed on setting itself up: office, staff, systems, processes, partnerships, and so on, producing little or no outputs. This was made possible by core funding from ACBF. Up until 2013 it still had core funding from ACBF as well as from the government of Zambia, complemented by project funding from DFID and the Danish Embassy.

NGO think tank

An interesting example is the Centre for Trade Policy and Development (CTPD), which was born from the secretariat of a network of NGOs, working on issues related to trade and development. This secretariat started by doing mostly capacity building work, but it slowly shifted towards policy analysis and influence. The network members then became a board or assembly for CTPD. The organisation receives funding from international NGOs (some of it core funding).

Political think tank

Zambia’s Patriotic Front, at a time when there was political leadership in the country, recognised that it needed to develop its programmatic capacity and decided that an external actor would help to monitor their progress and keep them focused. So, they created the Policy Monitoring and Research Centre [https://pmrczambia.com/]. One of the most interesting aspects is that it was created aid-free and not under the influence of NGOs (it did have short-term funding from DFID). The organisation started out with a staff of four (director and senior and junior research and communications officers) and grew from there.

Faith-based think tank

The Jesuit Centre for Theological Reflection (JCTR) has an interesting and uncommon think tank model: it is a faith-based organisation. It has the key advantages of having an established narrative and constituency. JCRT uses the Christian narrative, stories and metaphors, to communicate its evidence. This resonates strongly with many specialised and general audiences in the country. They have also developed a product: the basic needs basket. This is circulated and used in government, international actors, trade unions, media businesses, etc.

For more on religion and think tanks read these articles: Mendizabal (2012,) The church and think tanks and Mendizabal (2011), Is religion a ‘no no’ for think tanks?