Research

How will it carry out research?

Research is the cornerstone of a think tank. No matter the type of think tank, its aims, activities or business model, they all undertake some form of research. In this guide, we will not focus on research methods or type of research, but rather on how you can organise how it is carried out.

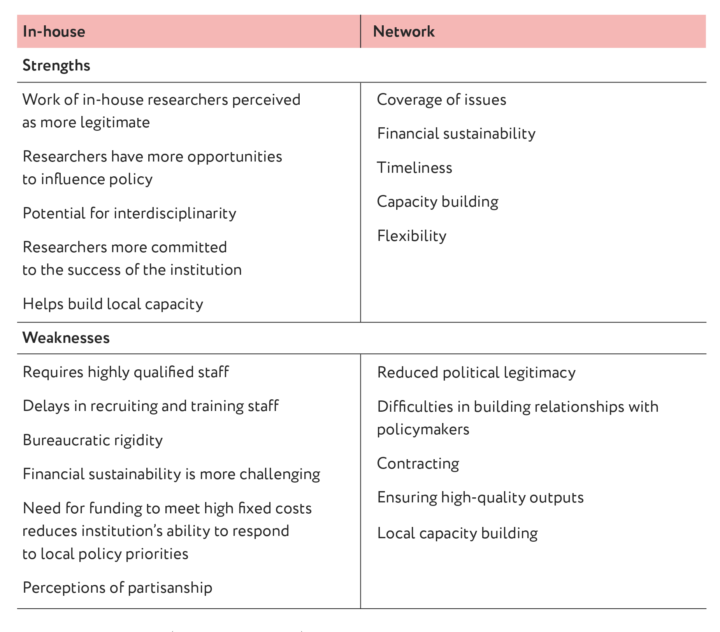

We have mentioned before that you can have researchers that are permanently employed by the organisation (in-house model) or work with external or associated researchers or consultants, national or international, hired to produce specific outputs (network model). Each has advantages and disadvantages (as seen in Table 1), and most think tanks rely not only on one or the other, but a mix of both (Yeo and Echt, 2018b).

Table 1: Strengths and weaknesses of the in-house and network models

Source: Extracted from Yeo and Echt, 2018b.

Earlier, we mentioned the two different research models: the solo star model vs. the team model. In the solo star model, notable researchers work independently with the aid of research assistants. The personal agendas of researchers largely influence the organisation’s work, and given their prominence and respectability in the sector, management staff have less power to shift the agenda. In the team model, team members work in coordination with other centres or consultants (or among themselves) to produce their work. Think tanks with a team structure tend to lean towards conducting large-scale research projects, programme evaluations, and so on. In this type of organisation, the research agenda tends to be more centrally determined by the organisation.

Box 38: Balancing own research and consultancies

In this video Lykke Andersen, one of the founding members of INESAD (Bolivia) explains how to balance commissioned work and long-term research.

How will you ensure that your research is policy relevant?

To be relevant to policy and practice, research needs to be embedded in its context. It needs to respond to existing problems and be recognised by the stakeholders involved (+)It might be the case though that a problem is not recognised by the stakeholders involved but considered important by the think tank. In this case, if the issue is considered to be important by the think tank, then one of its first tasks will be to elevate it in the public agenda and to the eyes of the actors involved. . If a research piece is either too general or too specific it might not be useful or find a space in the debate. Applied research, which is the sort that a think tank does, aims to find solutions to a problem and therefore needs to be timely. If not, it might miss the opportunity to inform policy (Ordoñez and Echt, 2016b).

To be policy relevant, research should follow these principles (Ordoñez and Echt, 2016b):

1. Be embedded in policy context.

2. Be internally and externally validated.

3. Be respond to policy questions and objectives.

4. Be fit for purpose and timely.

5. Be crafted with an analytical and policy perspective.

6. Be open to change and innovation: as it interacts with policy spaces and policymakers.

7. Be realistic about institutional capacity and funding opportunities.

Box 39: Toolkit for Political Economy Analysis

This toolkit is intended to help development projects achieve the best quality analysis and strong results: WaterAid (2015), Political Economy Analysis Toolkit.

Box 40: Policy questions are not the same as research questions

Based on Mendizabal, E. (2013f), Research questions are not the same as policy questions.

An important task for think tankers is working with policymakers to define what it is that they want to know and what information they need. If they focus only on what they say they want, a researcher misses out on uncovering what information is needed. A key skill for a think tanker is to unravel, with their stakeholders, what important questions need to be asked.

Policy questions are bigger in scope than research questions. To answer a policy question, many research questions need to be asked. For example:

Policymaker X might ask… But researchers might first have to answer …

⋅ What skills needed to be developed to take advantage of the rise of new trading opportunities? Are we facing more competition from other neighbours than in the past?

⋅ What specific sectors are under stress?

⋅ Which sectors seemed to be emerging as future opportunities?

⋅ What effects had domestic and international policy changes on these?

⋅ Are our trade policy strategies and regulations ready to address future challenges and threats?

Think tanks’ comparative advantage lies, or should lie, in translating policy questions into research questions and research question answers into policy question answers. To do this they must behave as boundary workers: simultaneously working in the policy and academic communities (Mendizabal 2013f).

Positioning your think tank for policy influence (+)Based on TT Insight ‘Positioning think tanks for policy influence‘ Learn more

The Think Tank Initiative (TTI) supported policy research institutions across the developing world for 10 years. TTI learned that a think tank’s policy influence is shaped by many factors, but two of these are key:

1. A reputation as an independent organisation that provides credible research.

Independence rests on organisational strengths, such as having financial sustainability.

2. The agility to navigate the local policy landscape and participate in policy debates.

Engaging with policymakers early in the research cycle helps to ensure uptake, so the think tank has to be agile in responding to shifts in the environment and choosing the right points of entry.

Think tanks can play a positive role engaging citizens, the media or advocates for marginalised groups directly in their research and in the policy process.

Therefore, achieving policy influence involves the entire organisation. The reputation for independence demands strengths across the think tank: effective leadership, financial sustainability, great researchers and administrators and the right skills in communications and networkers.

Research agendas (+)Based on Ordoñez, A. and Echt, L. (2016b), Module 1: Designing a policy relevant research agenda. From the online course: ‘Doing policy-relevant research’ and Weyrauch, V. (2015), Is your funding model a good friend to your research?

A research agenda is ‘a guideline or framework that guides the direction of the research efforts of an individual and/or organisation. It helps individuals and organisations communicate what they are focusing on and their area of expertise, and it also helps focus their research efforts and articulate different initiatives into common goals’ (Ordoñez and Echt, 2016b). It is not about producing a document and letting it sit. Research agendas are alive and active and they should guide the research that an organisation carries out. Agendas should be policy relevant, and for that they need to respond to the context.

When starting out you do not need to draft a lengthy document that outlines your research agenda (you can leave that for later) but it is a good idea to think about it, as it will give direction and purpose to your think tank. Your agenda should link to your aims and relate to your business model and funding strategies, as it will be affected by them. A think tank with core funding is freer to pursue their own interests, while contract or consulting think tanks tend to be more demand led.

When developing your research agenda, you should bear in mind the issues that interest you and the issues that are relevant in the context in which you wish to operate, but also the potential funding sources. The risk of building your research agenda in this autonomous way is that the topics and frameworks may not be completely linked to relevant stakeholders such as policymakers. On the other hand, funding based on grants or projects means you’ll have to be more flexible and open to addressing new topics or abandon others as you may have to adapt your agenda to donors’ priorities. Therefore, there is a trade-off between a more stable but less dynamic research agenda and a more flexible albeit less coherent research programme focused on projects.

Box 41. Components of a research agenda

There is no one specific way to draft a research agenda; depending on their characteristics and aims think tanks give prominence to different aspects. But in general, the following sections are recommended:

Contextual justification

Research priorities

Conceptual or ideological approach (if it exists)

Partnerships

Funding sources

How will it ensure the quality of the research? (+)This section draws from: Baertl, A. (2018), De-constructing credibility: Factors that affect a think tank’s credibility. Working Paper 4. Learn more (+)Doing policy relevant research. Learn more (+)Think Tank Initiative in Enabling success.

Research quality, in the evidence-informed policy arena, is more than caring and ensuring that the methodology and process of a piece of research is sound, ethical, rigorous and unbiased. The literature on the subject identifies many aspects to research quality:

- Clear purpose and fitness for purpose. The questions that the research seeks to answer should have a clear purpose (of influence or action) and the research methods applied should respond to it.

- Relevance for stakeholders and policy/legitimacy. The research should address the needs of the stakeholders involved.

- Integrity and scientific merit. This entails the technical quality of the research: design rigour, conclusions following from analysis, transparency, and following ethical guidelines

- Quality assurance processes. The organisation must ensure that the research they produce fits all these quality criteria.

Box 42. The role of the research director

Diana Thoburn is the director of research at CAPRI, a public policy think tank in Jamaica. She was interviewed by Annapoorna Ravichander in 2020. Read the full interview here.

My role as director of research is, broadly, to ensure that all the research we do and the reports we produce are done to the highest methodological and editorial standards. More specifically, I participate in determining our research agenda, conceptualising research projects, supervising researchers’ work from start to finish and editing the final report. I ensure that the organisation’s quality assurance protocol is adhered to and, as necessary, I engage in the research and writing myself. Finally, I represent the organisation in a variety of arenas, including presenting research results, whether on the media, to closed audiences, or at our public fora.

Options for ensuring research quality

Breaking down research quality into its component parts helps with planning for how to achieve it(+)We recommend exploring the Research Excellence Framework Learn more(+)and the RQ+ Learn more. For starters, working on developing a policy-relevant research agenda (+)For more on this you can inquire read the series Doing policy relevant research Learn more, as we discussed earlier, can help you identify gaps where research can be helpful. It can also help ensure that the research you will do is relevant to its stakeholders and to define the purpose of the research.

One thing you can do is work on developing a peer review process. This does not need to be applied to every piece of research that you do, but for important work you could have an internal peer review process in which researchers comment on each other’s work. Or you could have an external advisory group to advise on your research, not only after it is finished, but to ensure quality through the process (+)For more on peer review process read the series Peer reviews for think tanks Learn more.

You could also seek to collaborate with other research partners and academic institutions, especially on topics where you do not have internal capacity. This could help train your team and improve your organisational skills on specific subjects and research methods.

Finally, you should strive to develop a culture of evidence and quality data from the beginning. Discuss this with your team from the early stages and aim to grow and expand your quality control mechanisms as your organisation grows. Openly share your quality control mechanisms. This will be a signal to your partners and stakeholders that you produce quality research (+)Read the section on How will it ensure its credibility for more on this. .

Box 43: Do I need a peer review process?

The short answer is no, you do not need one. But it is a good idea to set one up for important work, and also to monitor the quality of your work and improve it. Setting a peer review process up also establishes an internal frame of mind that values and cares about research quality. It also signals credibility to your stakeholders (if you communicate it).